Human rights for African Americans were officially recognized in the U.S. with the historic passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the implementation of the Voting Rights Act a year later. Despite those historic legislative accomplishments, the IAM understood that centuries of racial discrimination had caused devastating social and economic damage in black communities. In response the union implemented an aggressive agenda in the 1960s aimed at uplifting minority workers.

The decade began with a public show of racial solidarity in late 1962 when then IAM President Al Hayes was publicly photographed warmly meeting with Martin Luther King Jr. at a banquet in New York City. Hayes, along with 1,500 labor leaders, welcomed the civil rights icon at a gala celebrating the 25th anniversary of the National Maritime Union.

Machinists viewed King Jr. as transformational leader and the face of the civil rights movement. But the union knew racial equality wouldn’t become successful without minority participation in labor’s grassroots ranks. IAM Shop Steward training played a critical role. A prime example occurred in January of 1963 when Lodge 1781 in San Mateo, CA announced that a multiracial group of members successfully passed the Stewards Training Course. The six-session class would certify at least a hundred.

By 1964 the Machinists Union continued to make organizing gains in cities with large African American populations. That winter then President Hayes presented a charter to new Lodge 814 in Washington, D.C., which would become a union hub to at least 600 taxi cab drivers. Many of whom were black including William Thompson who served as the local’s Vice President.

As membership grew, the IAM Executive Council saw a need to boost recruitment and groom a new generation of high-level leaders. In early 1965, Machinists offered 15 schools across the country where members could learn about organizational leadership. The training would be especially important as locals with large African American membership began to flourish such as Local 2013 in Richmond, VA.

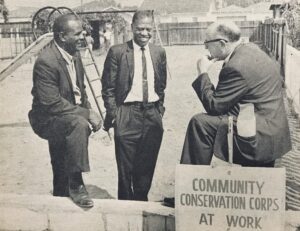

But in August of that year, the IAM would be tested as racial rage and anger spilled into the streets of Watts, CA where six days of rioting occurred after an African American man was brutally beaten by police. 14,000 National Guardsmen were called in after civil unrest caused $40 million in damage, 34 deaths and destroyed countless businesses. In response Machinists would help rebuild the broken community with the IAM-sponsored Watts Labor Community Action Committee. Under the leadership of a respected, up-and-coming, African American Grand Lodge Representative named Herb Ward, the organization was able to tap into hundreds of thousands of dollars in funds that were used to provide jobs, training and skills for 1,600 at-risk youth in Watts.

Tragedy would again strike in April of 1968 with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. But the Machinists Union mission of racial equality moved forward as the union consistently secured good contracts that benefited African Americans. As was the case at General Dynamics in Fort Worth, TX where a multiracial group of 14,000 production workers from District 776 built military jets like the F-111 bomber. Machinists would also continue fighting for rights of wrongfully terminated black workers like Noland Bailey of Louisiana. Local 228 successfully reinstated his employment at an ammunition plant and won him $1,432.60 in back pay, a strong statement of racial equality in the 1960s deep South.